The UC regents [during the week of July 14, 2014) approved borrowing $700 million internally to help close a pension funding gap, bringing the total borrowed to $2.7 billion in a pension bond-like strategy with risks or rewards, depending on investment earnings.

Five years ago, University of California employers and employees were paying nothing into the pension system. In a remarkable contribution “holiday” that began in 1990, payments into the system dropped to zero and stayed there for two decades.

After restarting in 2010, the employer contribution to the UC Retirement Plan (UCRP) increased from 12 to 14 percent of pay this month and most employee contributions increased from 6.5 to 8 percent of pay, a total of nearly $2 billion a year.

But the steady increase of contributions that were once zero still falls short of closing the pension funding gap. Last year, UCRP had only 76 percent of the actuarially projected assets needed to pay pension obligations over the next three decades.

To help close the funding gap, UC borrowed $1.1 billion from its own Short-Term Investment Pool in 2011 and $937 million from external sources. The $700 million loan approved last week is from the short-term pool.

“This will enable us to keep the employer contributions at 14 percent (of pay), which has been a huge drain on the campus and medical center operating budgets,” Nathan Brostrom, UC executive vice president, told the regents.

The original projections were that employer contributions could reach 18 percent of pay or higher. The $700 million loan intended to cap contributions at 14 percent of pay is expected to aid long-term planning and ease the budget squeeze on other programs.

Brostrom said the UC actuary, Segal, expects the loan to allow the employer contribution to remain at 14 percent of pay until 2026, when it would begin to drop, reaching about 9 percent in 2040.

The UC Retirement fund, with assets valued at about $50 billion, expects to earn an average of 7.5 percent a year, the same as the California Public Employees Retirement System. Critics say the earnings forecast is too optimistic and conceals massive debt.

In what some call arbitrage, money borrowed at a low interest rate from the UC short-term pool (which earned 1.7 percent last year) and invested in the pension fund earns a profit if the return is the expected 7.5 percent or even a little less.

Last fiscal year the UC Retirement Plan fund earned 17 percent. “So that additional 15 percent is arbitrage that goes to shore up and support the UCRP,” Brostrom told the regents.

Regent Hadi Makarechian suggested that more of the $6 billion short-term pool be shifted to the higher-yielding pension fund, if that fits into a pending debt plan. Brostrom said another loan in the future might lower the 14 percent of pay employer contribution.

“I do feel we are on a little bit of a slippery slope here,” said Regent Fred Ruiz. “I think we have to be very cautious … The market changes from year to year, and if we don’t get the returns we need to have, then we are in great trouble.”

The state made the employer contributions to UC Retirement until 1990, Brostrom said. But that stopped when the state did not want to continue payments to a retirement system with a big surplus, a funding level of 137 percent.

After a decade without contributions, and with several modest pension increases, the funding level soared even higher, peaking in 2000 during a high-tech boom at 156 percent.

Then with the natural growth of retirees and two drops in the stock market during the last decade, notably a full-blown crash in 2008, the pension funding level plunged deep into the red.

“Hypothetically, had contributions been made to UCRP during each of the prior 20 years at the Normal Cost level, UCRP would be approximately 120 percent funded today,” a UC staff report said in September 2010.

The other two state retirement systems, CalPERS and the California State Teachers Retirement System, also cut contributions (though not as dramatically as UC) and increased pension benefits when they had surpluses during the late 1990s boom.

The CalSTRS actuary, Milliman, said last year CalSTRS would have a funding level of 88 percent, instead of 67 percent, if it had continued to operate under its 1990 contribution and benefit structure without the changes made during the boom years.

Last month Gov. Brown signed legislation phasing in a $5 billion CalSTRS rate increase over seven years, mainly for school districts, that will nearly double the current $5.8 billion annual contribution from the schools, teachers and the state.

The new state budget signed by the governor last month continues to pay the employer contribution to CalPERS for the 23-campus California State University, which is $543 million this year.

UC has been trying to get the state to resume paying the employer contribution to UC retirement. The regents were told last week there is some progress, mainly signs that the state is acknowledging an obligation to make the pension payments.

In addition to restarting pension contributions, UC began giving new hires lower pensions last year. The maximum pension benefit will be delayed five years for the new hires, a change expected to cut costs by about 20 percent.

The UC Retirement Plan was not covered by the governor’s pension reform for CalPERS, CalSTRS and 20 county systems, which also began giving new hires a lower pension last year by delaying some formula steps until a worker is four years older.

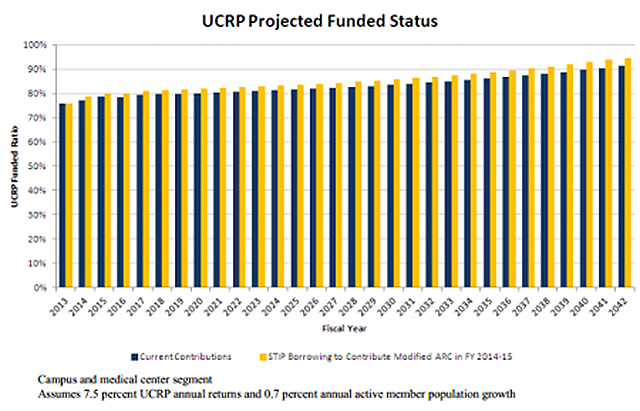

With the $700 million loan, UC Retirement is projected to be 95 percent funded in 2042, up from 91 percent without the new loan. The pension loans are being paid off with a campus and medical center assessment.

The assessment for the previous loans totaling $2 billion is 0.5 percent of pay this fiscal year, projected to grow to 0.55 percent to 1 percent over the next 10 years. The new loan increases the assessment to 0.72 percent this year, 0.8 to 1.35 percent over 10 years.

The UC faculty, as represented by the Academic Senate, supports borrowing to improve pension funding. A committee chair last month recommended a $1.7 billion loan, enough to fully fund UC Retirement.

Wall Street credit rating agencies support the use of loans to fund UC pensions, said Brostrom. In a Moody’s report this month on the growing pension burden of public universities and hospitals, UC is one of three universities mentioned.

A number of local governments have issued pension obligation bonds. A Center for Investigative Reporting analysis last fall found pension bonds are not panning out so far for Richmond and Pasadena and the counties of Merced, San Bernardino and San Diego.

A study issued by the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College issued in 2010 was based on $53 billion worth of taxable pension obligation bonds issued by 236 government agencies since 1986.

Most of the pension bonds issued since 1992 were in the red after the financial crisis, the study found. The issuers of pension obligation bonds often were fiscally stressed and in a poor position to handle investment risk.

“Nevertheless, it appears that POBs have the potential to be useful tools in the hands of the right government at the right time,” the study concluded. “Issuing a POB may allow well-heeled governments to gamble on the spread between interest rates and asset returns or to avoid raising taxes during a recession.”

This story was published by UCnet, reprinted from Calpensions.com.