From Gospel music sung in African American churches in the Deep South in the 50s to the traditional music and dances of the Tolowa and Yurok people of California, the UCLA Ethnomusicology Archive is a rare time capsule of past moments of music and dance from cultures around the globe.

Whether you want to see a spirited performance by the most sought-after tamburitza orchestra in the West in the ’60s, a mariachi medley led by the legendary Nati Cano in the ’90s or a lecture/demonstration of Southern rural music by Mike Seeger in 2008, you can see and hear all of these snapshots of musical history among the archive’s 150,000 recordings.

The 55-year-old archive is one of the largest ethnographic audiovisual archives in North America. There’s only one larger, and it’s in the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. At UCLA, the archive’s file cabinets and shelves brim with discs of all kind, videocassettes, video and audio reels, films, digital audio tapes and wire recordings, among other media.

“There’s not a continent in the world — except for Antarctica where no one lives — that’s not represented here,” said archivist Maureen Russell. Located in Schoenberg Hall and the UCLA Herb Alpert School of Music, the archive is part of UCLA’s Department of Ethnomusicology, the only academic department of its kind in the United States.

“Ethnomusicology is the anthropology of music,” Russell explained, the study of music in its cultural, historical, economic and linguistic context. “With the archive, we’re trying to preserve and maintain cultural memory. Cultures are defined by their cultural memory. So it’s very important to us that these materials be maintained.”

That’s a major problem with deteriorating magnetic media — reel tapes, cassettes and videotapes that make up about half of the archive’s holdings. But Russell has found a way to preserve a small portion by making them available for the first time to the public and scholars via the Web. She and her small staff have made some progress in their struggle to save some of the archive’s most significant materials that are relevant to California — through the California Light and Sound collection on the nonprofit Internet Archive.

Run by the California Audiovisual Preservation Project (CAVPP) in partnership with 75 libraries, archives and museums, the California Light and Sound collection of recordings offers a peek into the state’s rich audiovisual heritage and is a broad resource for teaching, research and study. So far, CAVPP has agreed to digitize 205 items from the UCLA archive; 55 of those were made available last year on the UCLA Ethnomusicology Archive “channel” on the California Light and Sound website. The rest will be posted sometime this year.

“One hundred percent of these 205 items were in danger of becoming unplayable,” said Russell, because they were all recorded on magnetic media. Each recording had to be nominated and documented by the archive staff before CAVPP would accept it.

But that’s only a small part of the archive’s entire collection, said Russell. Most experts estimate that the current lifespan of magnetic media is about 15 years or less. When these recordings will start to break down is anyone’s guess. “It could be tomorrow, it could be in 10 years. It could have already happened. We don’t know until we try to play it. But in all likelihood, our magnetic media will be unplayable for the class of 2025,” she said.

Sadly, almost all of the archive’s field recordings — the product of years of research by hundreds of UCLA faculty and graduate students of cultures around the world — are on magnetic media.

And the cost of digitizing and preserving these materials goes way beyond the archive’s resources. It’s a universal problem for many other institutions. Last month, for example, the British Library launched its “Save our Sounds” campaign to raise $61 million to digitize its audiovisual collection.

Not only are the recordings at the archive endangered, but some older formats like the U-matics — three-quarter-inch videocassettes — can’t be played at the archive because it lacks the mechanism to play it back. U-matics were included in the archive’s Don Ellis Collection, donated by Ellis’ heirs.

Ellis, once a graduate student at UCLA, was a well-known jazz trumpeter, drummer, band leader, recording artist and composer. Music composed for Ellis by Hank Levy was recently featured in the Oscar-winning movie “Whiplash.”

“These [U-matics] came to the archive with minimal documentation, so we didn’t know exactly what was on any of them other than what might be written on the tape label,” Russell said.

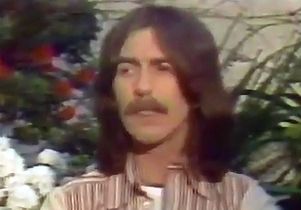

It wasn’t until Russell saw the digitized version of one such U-matic on the California Light and Sound website that she realized it showed Don Ellis interviewing Beatle George Harrison about his long collaboration with sitarist Ravi Shankar in 1976, his interest in classical Indian music and spirituality. Taped by KCET, the show included clips from Shankar’s concert at the Royal Albert Hall in London.

“That was a real surprise,” the archivist said.

All of the recordings available on the Internet and in the archive came from donors, UCLA faculty and graduate students, and community members. “The archive holds UCLA ethnomusicology lectures and concerts dating back to the early ’60s,” said Russell. “It’s really UCLA Ethnomusicology’s institutional memory.”

Some eclectic highlights from the archive’s channel:

- The Ash Grove’s 50th anniversary celebration at UCLA. For 15 years — from 1958 to 1973 — this nightclub in West Hollywood was a mecca for more than 100,000 Angelenos who came to hear Linda Ronstadt, Lenny Bruce, Joan Baez and Jerry Garcia, among many others. In 2008, the ethnomusicology department joined forces with those who once ran the now-defunct Ash Grove for a weekend of concerts, workshops and discussions. Here, Holly Near, a singer-songwriter with a long career in folk and protest music, explores the relationship between songs and activism with her guests.

- Bird songs of the Cahuilla people, the first known inhabitants of California’s Coachella Valley. Recorded in 1987 by former ethnomusicology graduate student Brenda Romero and others, the songs tell the creation stories of the Cahuilla, who compared their arrival on Earth to the migratory flights of birds.

- Don Ellis and his band perform at Ellis Island, a club on the Sunset Strip in 1967. In the opening sequence, the camera pans over the glamorous nightclub scene outside Dino’s Lodge, Sneeky Pete’s, The Whisky and other hotspots along the Strip.

- Here’s your chance to see students and faculty at the then-UCLA Institute of Ethnomusicology in action. In “A World of Music,” a 1972 documentary made by UCLA’s Public Information Office, students and faculty demonstrate their mastery of international musicianship by playing works from Java, Bali, Thailand and Ghana on instruments from those countries. See if you can recognize a few now-senior scholars in their graduate student days.

- UCLA Music of Mexico Ensemble and Mariachi Los Camperos de Nati Cano directed by the legendary Nati Cano. Based in L.A., Cano revolutionized the mariachi sound by blending older, traditional rhythms of mariachi with harmonies from this country’s and Mexico’s popular music. The UCLA Music of Mexico ensemble was one of the first mariachi groups to be formed at a university.

Coming soon will be audiovisuals of band leader, composer and percussionist Tito Puente; trumpeter John Birks “Dizzy” Gillespie; and lectures on and examples of African American Gospel music.

“So stay tuned,” said Russell.