A researcher at the UCLA Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center helped develop a combination drug therapy that was approved today by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat metastatic melanoma. The therapy shows great promise for extending the lives of people with an advanced form of the disease, and it does so without causing a secondary skin cancer, a side effect seen in some patients who took only one of the drugs.

The study was conducted at UCLA and 135 other sites in the U.S., Europe, Australia and Russia.

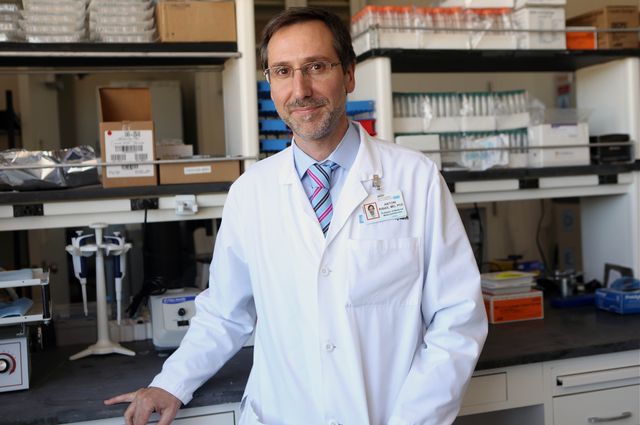

“Today’s approval is a very significant advance in the treatment of metastatic melanoma,” said Dr. Antoni Ribas, the study’s senior investigator and a researcher at the Jonsson Cancer Center. “For patients with a BRAF mutated melanoma, the combination has higher activity to shrink their tumors, and with less side effects than the drugs on their own.”

The drugs, vemurafenib (marketed under the brand name Zelboraf) and cobimetinib (Cotellic), were tested in combination on approximately 495 patients who had BRAF V600, a mutation-positive advanced melanoma. Because so many of the people in the early stages of the study showed significantly better responses than those who had been prescribed vemurafenib alone, the study was continued and the FDA granted the therapy “priority review” status, leading to its approval.

An estimated 70,000 people in the U.S. are diagnosed with melanoma annually in the U.S., and 8,000 people die of the disease each year. About half of the people with metastatic melanoma have a mutated protein called a BRAF mutation.

This mutation can be treated with vemurafenib, which was recently approved by the FDA. Researchers previously discovered that the BRAF mutation gives melanoma the signal to grow continuously as a cancer, but vemurafenib taken by itself cannot completely block that signal.

The new study showed that when the experimental drug cobimetinib is added, the combination slows the growth of the melanoma, Ribas said.

In addition, prior research had found that 25 percent of patients who had been given vemurafenib alone developed a secondary skin cancer. But in the new study, combining cobimetinib with vemurafenib decreased the incidence of secondary skin cancer.

Kenneth Dorshkind, interim director of the Jonsson Cancer Center and a professor of pathology at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, said that although there have been significant advances in treatment for metastatic melanoma in recent years, there is still a great need for effective new therapies.

“When melanoma is diagnosed early, it is generally a curable disease, but most people with advanced melanoma have a poor prognosis,” Dorshkind said. “Based on upon the pioneering work conducted at UCLA, we are making significant advances against this deadly disease and people have more treatment options.”

The study that led to the FDA approval of the combination therapy built upon prior studies led by UCLA’s Dr. Roger Lo, a Jonsson Cancer Center member and associate professor of medicine, whose research showed how melanoma became resistant to vemurafenib and how the addition of a drug like cobimetinib could overcome that resistance.

Ribas, who also is a professor of medicine in the division of hematology-oncology at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, said ongoing research will be aimed at improving the therapy’s effectiveness.