History has not been kind to the Owens Valley.

Indigenous people called the Owens Valley “Payahuunadü,” or the land of flowing water, and settled along the banks of its river, creeks and springs more than 150 years ago. In the early 1900s, the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power took control of the valley’s rich natural resource, which streamed through the plains at the foothills of the Eastern Sierra, to sustain an expanding megalopolis 200 miles south.

In 1942, the now dry, dusty valley became the infamous site for the Manzanar concentration camp, where more than 11,000 Japanese Americans were incarcerated until 1945.

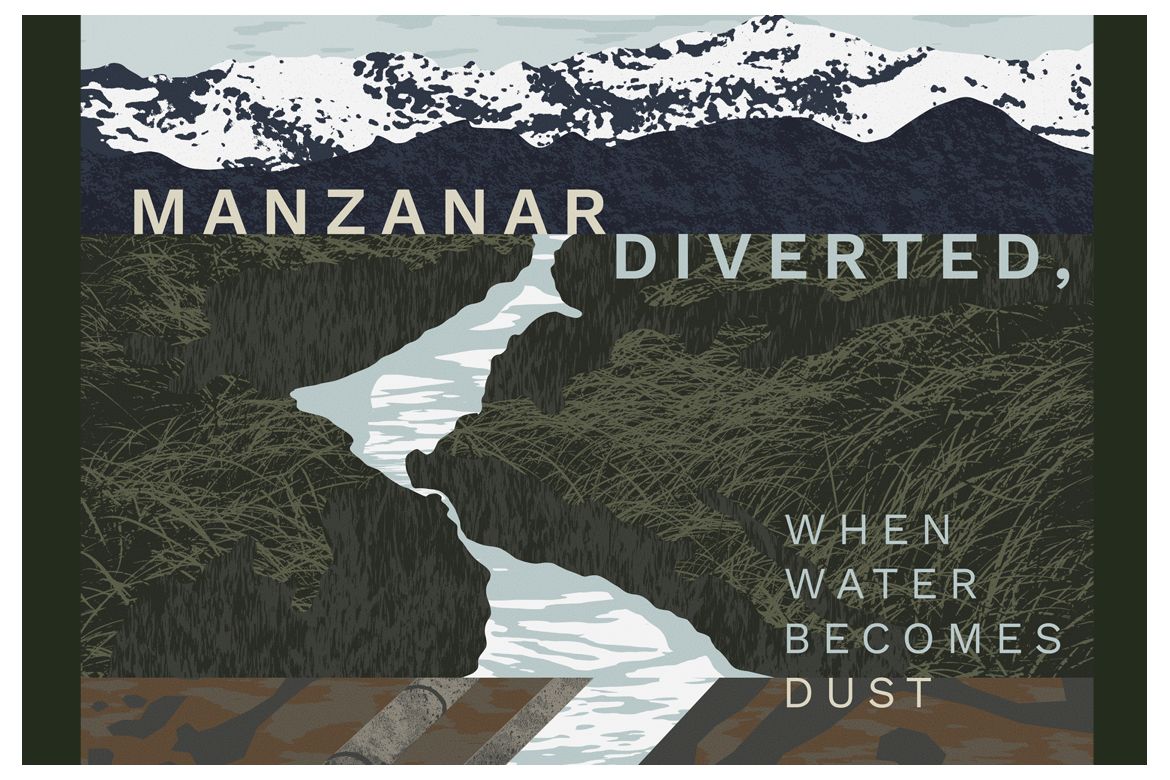

Bringing all these complex histories together is “Manzanar Diverted: When Water Becomes Dust,” an enlightening documentary about the Owens Valley’s sad legacy of colonization, racism and environmental assault, as well as the 21st-century fight to preserve the valley’s land and water resources.

The filmmaker and producer behind “Manzanar Diverted” is Ann Kaneko, a lecturer who earned a master of fine arts degree in film directing at the UCLA School of Theater, Film and Television.

Kaneko, an Emmy Award winner whose documentaries have screened internationally and have been broadcast on PBS, serves as an artist mentor for emerging Asian Pacific filmmakers. She has been a Fulbright and Japan Foundation Artist fellow and has been commissioned by the National Endowment for the Arts, the Skirball Cultural Center, the Japanese American National Museum and the Getty Center.

Nearly six years in the making, “Manzanar Diverted” had its world premiere this past weekend at the Big Sky Documentary Film Festival. It will screen again online on March 7 at 1 p.m. PT at the One Earth Film Festival, based near Chicago. There will be a live Q&A following the screening with Kaneko and two others who appear in the film.

“The film is an attempt to make sense of this history and share with audiences an understanding of how this valley, so far from Los Angeles, has had such profound connections to me and my community,” Kaneko said.

The filmmaker has a personal connection to the federal government’s forced removal of American citizens of Japanese ancestry during World War II: Her parents and grandparents were incarcerated in two concentration camps in Arizona.

But there is also a broader connection that links every Angeleno to the Owens Valley. Not only did the Los Angeles Aqueduct’s diversion of water suck the valley dry, but “it turned Owens Lake, once the fourth largest lake in the state, into a source of air pollution … because of the toxic dust that comes off this place,” Kaneko said. “I don’t think people are really aware of the impacts our lives are having on other places.”

Her film also illuminates another dark chapter in the history of the government’s unjust removal of a whole community.

Decades before the Manzanar camp was built, ranchers and homesteaders who settled in Owens Valley clashed with the Nüümü (Paiute) and Newe (Shoshone) peoples over land use issues. “The Indigenous people were being starved out because cattle were trampling their land and food sources,” Kaneko said. In 1863, the U.S. Army tricked these tribal communities into gathering at nearby Camp Independence and then marched them out of Owens Valley to Fort Tejon, nearly 200 miles away. Many, however, were able to return on their own.

Owens Valley was subjected to another “removal” at the hands of government officials when whole communities were uprooted by the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power in a land grab. The department now owns about 90% of the valley.

“When the DWP bought out the valley, many people were basically forced out because they could no longer make a living there,” Kaneko said. “The circumstances were different [from the Indigenous people], but these are similar histories of development and colonization. And then, of course, you have the Japanese American incarceration.”

Kaneko tells these layered stories principally through eyewitness accounts and the shared memories of Native Americans, incarcerees and community leaders. As their stories unfold, there are moving scenes of vacant and brush-strewn land, water rushing through the aqueduct and gushing from a public park fountain in L.A., and archival footage of what once existed at the Manzanar National Historic Site.

Kaneko, who remembers visiting Manzanar with her parents as a child, said she has always been mesmerized by the raw beauty of the long stretches of desert along Highway 395. “I always wondered why there was no development there,” she said.

She had the opportunity to look more closely into the area’s history in 2014. A colleague, who teaches Asian American studies at UC Irvine, invited her to join a group of humanities scholars on the annual Manzanar Pilgrimage, which brings together incarcerees, their descendants, social justice activists and the public to reflect and learn about what took place there.

As a result, “Manzanar Diverted,” Kaneko said, “is through and through a collaborative work with UC scholars.”

At first, Kaneko wondered about the kind of film she could make about Manzanar, a national symbol of racism and injustice. “There have been so many amazing films that have already been made about it,” she said.

But the more she learned, the more she became intrigued by the connections between the Indigenous communities, the Manzanar camp and their shared history of forced removal. For example, she found out that many of the camp administrators were former Bureau of Indian Affairs staff.

She also learned that the federal government initially planned to house all Japanese Americans living on the West Coast in Owens Valley. But the site required water so that incarcerees could grow their own food, and the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power balked at the plan, which would leave the nearby aqueduct open to possible sabotage, among other concerns.

Instead, the federal government commandeered only a square mile of land for the camp. Water from a nearby creek, which originally fed into the aqueduct, was siphoned off to fill a reservoir for the camp.

With their extensive knowledge of horticulture and agriculture, the incarcerees built stone-lined fish ponds and Japanese-style gardens, turning the wind-blown desert into a more hospitable place to live. “People were looking for a way to make the best of things,” Kaneko explained.

But Kaneko wanted “Manzanar Diverted” to be more than a historical retrospective. “I really was keen to bring it to the present,” she said, “so that people could understand that this is an ongoing issue.”

Therefore, the film delves into a successful grassroots fight in 2013–15, which united Native Americans, advocates for the Manzanar site and local residents to block the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power’s proposal to build large-scale solar facilities in Owens Valley.

By drawing on the past and present, the film builds “an awareness of the connection between the urban areas we live in and these rural areas we’ve colonized, where our resources come from,” she said. “Our water comes from this place, and it comes at a cost. That’s true for other sites around the world, some of which have also been turned into deserts in service to growth.”