William Worger, professor of history at UCLA, has spent his career specializing in the social and economic history of South Africa. During his first trip to the country in 1977, the government exercised strict censorship over all media. In the aftermath of the June 1976 Soweto student protests against apartheid, and the police killing of the Black Consciousness leader Steve Biko in September 1977, many newspapers and magazines were banned, and any story about anti apartheid protests literally blacked out with censors’ marker pens. Ironically, two pro-government publications had already disappeared, burned by the Soweto students.

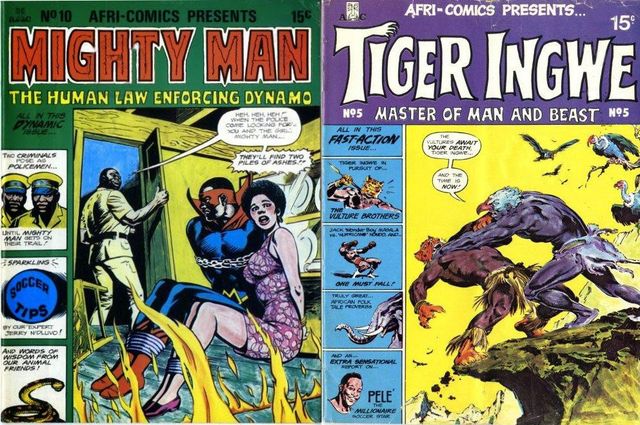

“Mighty Man,” one of the two, was a secretly commissioned comic series published by the South African government, with the help of the CIA, as a propaganda tool during that time. Intended for younger audiences in the capital city of Johannesburg, “Mighty Man” featured a former policeman who fought crime and helped those in trouble. The other comic, called “Tiger Ingwe,” (the titular character is half man, half beast) sought to appeal to people in South Africa’s rural communities. Both promoted pride in African heritage and had a strong focus on law and order, which Worger points out, was a message that indirectly supported the apartheid government. That message backfired when the students burned these propaganda tools.

Though the comics seemed to disappear from the public arena with none listed in any library collection worldwide, traces of them remained in the world of comic collectors, which is where Worger found reference about four years ago to the existence of a few copies. As he continued to search for more copies, he discovered a small collection being sold as part of the estate of a deceased New York comic collector. Since then, Worger has collaborated with the UCLA Library to create a digital archive that is now available to the public.

Earlier this year, Worger visited South Africa again to dig deeper into these Afri-Comics and shared his latest findings and research in a recent email interview with UCLA Newsroom.

How did you find these comics and what about them drew your attention?

I have been carrying out research on South Africa since the 1970s when I first visited that country to do research for my Yale Ph.D. in history. Part of that research has been investigating the career of a young African who was taken into police custody in December 1976 and who died the day he was apprehended, most likely killed by the police suppressing political dissidents. Another part of the research has been examining the cultural side of state-sponsored white supremacy, as found in government publications, and the resistance to that by anti-apartheid activists through various forms of media. One of the key features of that period was the extent of government censorship. It was a criminal act, for example, to quote Nelson Mandela in any publication, and the apartheid government was seeking internal and overseas support by disguising some of its publications as being produced by independent third parties. Such was the case with Afri-Comics, published by a “front” company secretly funded by the South African government.

What was the purpose of these comics and their main characters?

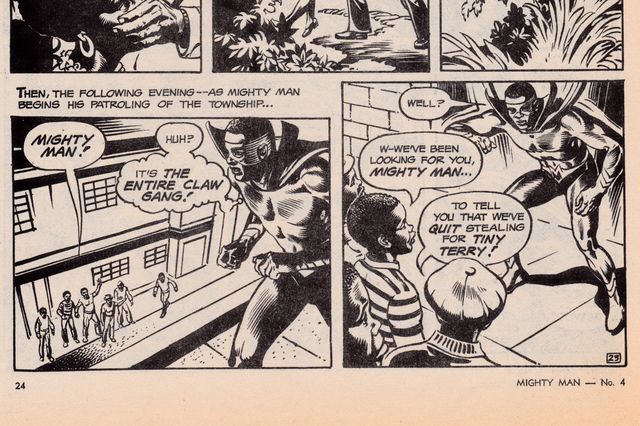

The comics had two audiences. One title, “Mighty Man,” was intended for urban black audiences, especially the youth who lived in communities such as Soweto, the huge black township southwest of Johannesburg. The second title, “Tiger Ingwe,” was meant to appeal to young Africans living in more rural parts of South Africa. The main characters combined an emphasis on pride in their African heritage, expressed through such means as stories drawn from African folklore, and recreational interests, such as boxing, together with a stress on the need to fight crime and uphold law and order, which was essentially a proxy for supporting the apartheid government but without explicitly saying so.

How did the public react when “Mighty Man” and “Tiger Ingwe” were published? Why do you think they got the reaction they did?

There are a number of different reactions, reflected in some of the discussions that I have had this past summer in South Africa with people who were in their teens in the mid-1970s. With some — and they are now in their mid-50s — they have emphasized their lack of interest in comics in their early teen years when they say they were much more focused on politics. Others have said they read the comics simply as entertainment.

As I was reading volume 1, I noticed it portrays a typical theme in which superhero defeats criminal. I’m curious to know if this seemingly usual and what I believed to be a universally agreed upon idea that crime is bad was a form of propaganda and if so, how?

When you look closely at the “Mighty Man” issues you can see that there were very particular references to life in Soweto — the types of houses, the occupations, etc. — which makes it clear that the comics do not simply embody a universal anti-crime message, but have a very specific intention, and that is to emphasize the linkage of anti-crime and pro-government positions. Not explicitly pro-apartheid since that would have been universally rejected, but very much a linkage of law and order with support for authority. Let’s take a different example, a series of “Black Panther” comics published in 1989, very anti-apartheid, anti-white supremacy in approach, very specific and factually correct in their depiction of life in South Africa, and emphasizing that the criminal activities in South Africa were those of the apartheid government and its supporters.

While I was researching the origin of these comics, I found that they were a collaboration between the South African government and the CIA. How did the American government get involved? Did they know they were helping an apartheid government that believed in institutionalized racism?

There is a long history of American — CIA specifically — intervention overseas during the height of the Cold War era, especially in the 1950s through the end of the 1980s. The U.S. government through its own “front” agencies published a great deal of material that was distributed overseas and that denounced critics of many authoritarian regimes, including that of apartheid South Africa, as essentially pawns of the Soviet Union. That explains why so many people during that period in the U.S. and elsewhere referred to the African National Congress (ANC) as a Soviet front, and to Nelson Mandela as a stooge who had engaged in criminal activity. Indeed, the CIA itself was suspected, though as yet this has not been proven, as being complicit in Mandela’s arrest in 1962, and also in the still unresolved death of the ANC leader, Albert Luthuli, in 1967.

I also found that DC Comic artists were responsible for illustrating “Mighty Man” and “Tiger Ingwe.” How did they also get involved? Do you think it was hard for American illustrators to even know how to create a style that would appeal to their South African audience? Could this have related to the comics’ demise?

This is a topic that I am still researching. The DC illustrators are no longer alive, and it appears that they have left no documents detailing their participation in the South African government project. It appears that they were contracted to do the work in their own time, so their activities were not in any way related to their full-time DC Comics jobs. In the South African documents there are references to the need to have the American artists draw the superheroes as “African in appearance,” though what that meant specifically I have not yet determined.

Now that you’re spearheading a project at UCLA to digitize these comics and make them available to the public for free, what do you hope to achieve with this archive?

The importance of the project for people in South Africa — the people to whom these comics were originally targeted — is to enable them to engage in multiple ways with an essential part of their history that to date has been hidden. For the readers like the ones I mentioned above, for example those who did not read the comics but were already reading politically focused newspapers, it has been something of a revelation to see how sophisticated the government propaganda was that had attempted to target them, and to see how the white supremacists had created texts which combined folklore and sports and anti-crime stories into a complicated text which sought surreptitiously to get into the minds of their peers. For others, like those individuals who had enjoyed reading the comics as entertainment in the mid-1970s, being able to read them again (I shared paper copies while I was in South Africa, and then showed people how they could read all the issues for free on the UCLA YRL website) was something they enjoyed doing. It’s as though you discovered again part of your youth, but part that had been lost. Because how many of us, other than avid collectors, keeps much of the material that we read when we were kids?

What’s something you hope people today can take away from these comics?

Being aware of how constant and how persistent governments can be (other countries’ and our own) in attempting to manipulate how we think, and doing so in secret ways. Manipulation of public opinion via Twitter and Facebook is nothing new. And comics are one example of the long history and persistence of such practices.