UCLA, which turns 100 years old on May 23, came into existence just after World War I, on the eve of the 1920s boom in American prosperity and confidence. A decade later, as the Depression began, UCLA moved from Vermont Avenue in Los Angeles to a new place on the map, Westwood — on the leading edge of a population explosion that pushed the city’s destiny toward the ocean.

The first UCLA century is remarkable on any scale. It looks all the more impressive when you know that the campus thrived in spite of intercampus jealousies and passionate opposition from the hallowed home ground of the University of California in Berkeley. That UCLA happened at all is proof of the hubris and ambitions that fueled the growth of Los Angeles into a mega-city.

Creating a southern campus of Berkeley was the subject of a strategic lunch conversation on Oct. 25, 1917, at the exclusive Jonathan Club in Los Angeles. Edward Dickson, on one side of the table, was an editor and the future publisher of the Los Angeles Express newspaper. Ernest Carroll Moore was the president of the Los Angeles State Normal School, the state’s largest training school for teachers. Dickson had been a student of Moore’s years earlier at Berkeley.

Their dreams for the future aligned: growing Southern California needed a state university. Los Angeles already had more people than San Francisco and sent more freshmen to the University of California up in Berkeley than any city. The clamor for higher education opportunities in Los Angeles was loud and growing louder.

“A full-fledged university”

Dickson was on the inside: He was the only member of the University of California’s governing Board of Regents from Southern California. People in power would at least listen to him. Moore had resigned from the faculty at Harvard to move back to Los Angeles, explaining that for him, like so many at the time, “California is an incurable disease.” He had a creative proposal for his former student.

Moore would support aligning the Normal School, which had a relatively new campus on North Vermont Avenue in Los Angeles, with Berkeley. Instead of merely training elementary school teachers, he saw the new institution granting bachelors degrees in education. Training those who would train teachers. Dickson liked the idea enough, but he believed in a grander vision.

“I was not greatly interested in a teachers’ college,” he wrote later. “My ultimate objective was a full-fledged university.”

The two men agreed to be co-conspirators, pushing together toward establishing the university that Los Angeles so obviously needed. They were fought by the president of Berkeley, many of the faculty and most of the regents, who all feared dilution of Berkeley’s preeminence and the draining of talent, top students and tax dollars. Battles were heated and ugly, but some regents could see the future coming.

The 1920 U.S. census would tectonically shift political power in California toward the booming population of the south. If the university didn’t act on its own, the politicians soon would. Delicate negotiations, and a new governor more inclined toward the south’s concerns, led to a carefully arranged deal.

On May 23, 1919, Gov. William D. Stephens signed into law Assembly Bill 626, creating the Southern Branch of the university and transferring to the Board of Regents the 25-acre Los Angeles Normal School campus at 855 North Vermont Avenue. The Normal School, operating since 1881, would pass out of existence and a new institution would appear, the University of California Southern Branch, with Moore as its first director and later provost. Most students would still focus on education studies, but there would be general college courses for freshmen and sophomores. Students would need to spend the final two years at Berkeley to get their bachelor degrees.

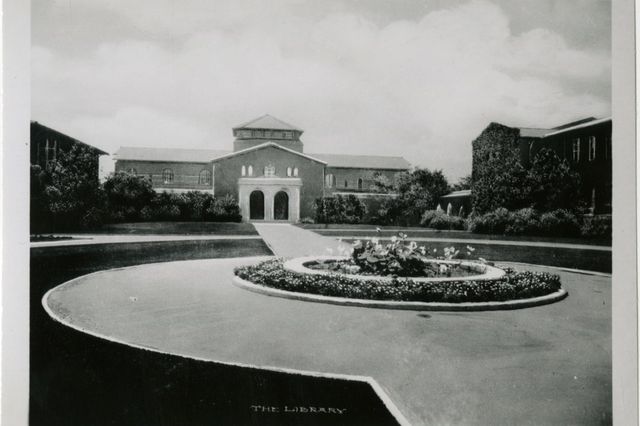

The Southern Branch opened on Sept. 15, 1919 with 1,213 women and 207 men enrolled. Demands for seats far outnumbered the available spots. There were no residence halls. Instead, students took the city’s Red Cars and Yellow Cars to the campus, a pretty facility with red-brick buildings in the Lombard Romanesque tradition designed by Los Angeles architects Allison and Allison, with green lawns, eucalyptus and acacia trees, and ivy-covered walls. Female students could not complete their class registration until the dean of women approved their living arrangements.

More tense and often petty clashes with Berkeley followed — over budgets, hiring and academic status — before the Southern Branch found its footing and was allowed to offer university degrees. The first group of 28 graduates received their bachelor of education diplomas in June 1923. Two years later, the first bachelor of arts degrees were awarded to 98 women and 30 men by the new College of Letters and Science. Two years after that, the senior class valedictorian was Ralph Bunche, later to become the first African American (and only Bruin) recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize, for his diplomacy in the Middle East as a representative of the United Nations.

By the year that Bunche graduated, the College of Letters and Science already ranked as the nation’s fifth largest liberal arts college. Students overwhelmed the campus. Dickson and Moore pressed, at Berkeley and in the state capital, the need for a bigger permanent home for the Southern Branch.

On to Westwood

The university regents knew that the future UCLA would need a new campus — a home that was up to the call to greatness already infusing the young institution. They turned for advice to a committee of Los Angeles civic leaders led by attorney Henry W. O’Melveny.

Interest from several cities was investigated and the final candidates for a new campus narrowed to locations in Burbank and Pasadena, Fullerton in Orange County, and on the Palos Verdes Peninsula near the Port of Los Angeles. Dickson, a growing voice among the regents and in Los Angeles civic circles, favored a fifth site, on a grassy slope west of the small enclave of Beverly Hills, 13 miles from downtown Los Angeles and well beyond the city limits.

The land, originally within the 4,400-acre Rancho San Jose de Buenos Ayres granted to Don Maximo Alanis, a Spanish soldier and settler of the Los Angles pueblo, had gorgeous views of the Pacific Ocean and the Santa Monica Mountains and reminded Dickson of Berkeley’s setting. Significantly, the Letts tract, named for a previous land owner, lay in the direction of Los Angeles’ inevitable westward expansion across the coastal plain.

Real estate developers Harold and Edwin Janss owned the land and they had dreams for a new community, Westwood, to grow adjacent to the university. They foresaw homes for tens of thousands of families, movie studios, and a shopping village that would rise into “one of the most unusual business districts in the United States.”

Furious politicking carried on behind the scenes, until on May 21, 1925, the Board of Regents formally voted in favor of the Letts tract, also called the “Beverly site.”

“The site was chosen generally because it was believed be in the trend of population growth in Los Angeles, and to have available excellent transportation facilities,” the regents said. “The splendid topography and climate of the site chosen were also compelling arguments in its favor.”

Not everyone was impressed. “The campus is so far out in the country that it’s obvious only farmers will ever be the students’ neighbors,” a newspaper observed at the time.

A condition imposed by the regents put up a daunting obstacle. State money raised through bond issues would help pay for construction, but the regents required that acquiring the land not cost the University of California anything. That was a problem since the Janss brothers wanted to sell 300 acres for $2,000 each, and another 75 acres for $7,500 each. The land was worth much more on the open market, they argued.

A remarkable election campaign within the cities of Los Angeles, Beverly Hills, Santa Monica and Venice needed to convince voters to approve bond measures to cover the cost of the land.

High school and college students campaigned on radio stations and showed a 10-minute film in movie theaters to persuade voters. The film, “College Days,” depicted tearful farewells at train stations as sons and daughters went away to college. “The clear message,” said the history book “UCLA: The First Century,” was that “such sad partings would be unneccessary if an adequate local institution were available.”

A giant bonfire and rally was held in Westwood the night before the election, and more than 2,000 students were stationed in pairs near polling places to make sure the message was heard. On May 5, 1925, Proposition 2 passed in Los Angeles by a nearly 3-to-1 yes vote.

Voters in the other cities also agreed to tax themselves. The University of California at Los Angeles, the new formal name, was now destined to rise at the center of a new Los Angeles region. (The name University of Beverly was also considered.)

In February 1926, a 75-ton granite boulder was trucked over 10 days from a quarry in Perris Valley and placed on the wild hillside west of Beverly Hills. Founders’ Rock was the idea of Edward Dickson, and the ceremony celebrating its placement marked the symbolic start of construction on the new campus.

“Each person there tried to imagine what the open barley field would soon look like and no one succeeded,” Ernest Carroll Moore wrote in his diary.

In May 1927, work began on a bridge spanning the shallow arroyo that spilled through the acreage. The bridge would open the site to construction workers — and soon after to students and professors. It was considered such a monumental step in the creation of the UCLA campus that California Gov. C.C. Young attended the structure’s dedication on Oct. 22, 1927. The future was beginning.

This story is based mainly on two UCLA history books published by the UC Board of Regents: "UCLA On The Move" (1969) by Andrew Hamilton and John B. Jackson; and "UCLA: The First Century" (2011) by Marina Dundjerski.