After 10 weeks sputtering around Cameroon in a dilapidated Land Rover, Tom Smith had seen just one black-bellied seedcracker.

The Central African species of finch — intriguing from a research perspective because of unusual variations in bill size — was central to Smith’s doctoral research at UC Berkeley in the early 1980s.

The Land Rover’s brakes did not work, something Smith discovered on a downhill slope. The resulting collision took the bumper off a passenger van. A few days later, a wheel flew off and bounced into the jungle, taking hours of machete work to recover.

But with just two weeks remaining on his first expedition in Africa and no birds to show for all the trouble, somehow Smith’s own wheels didn’t come off.

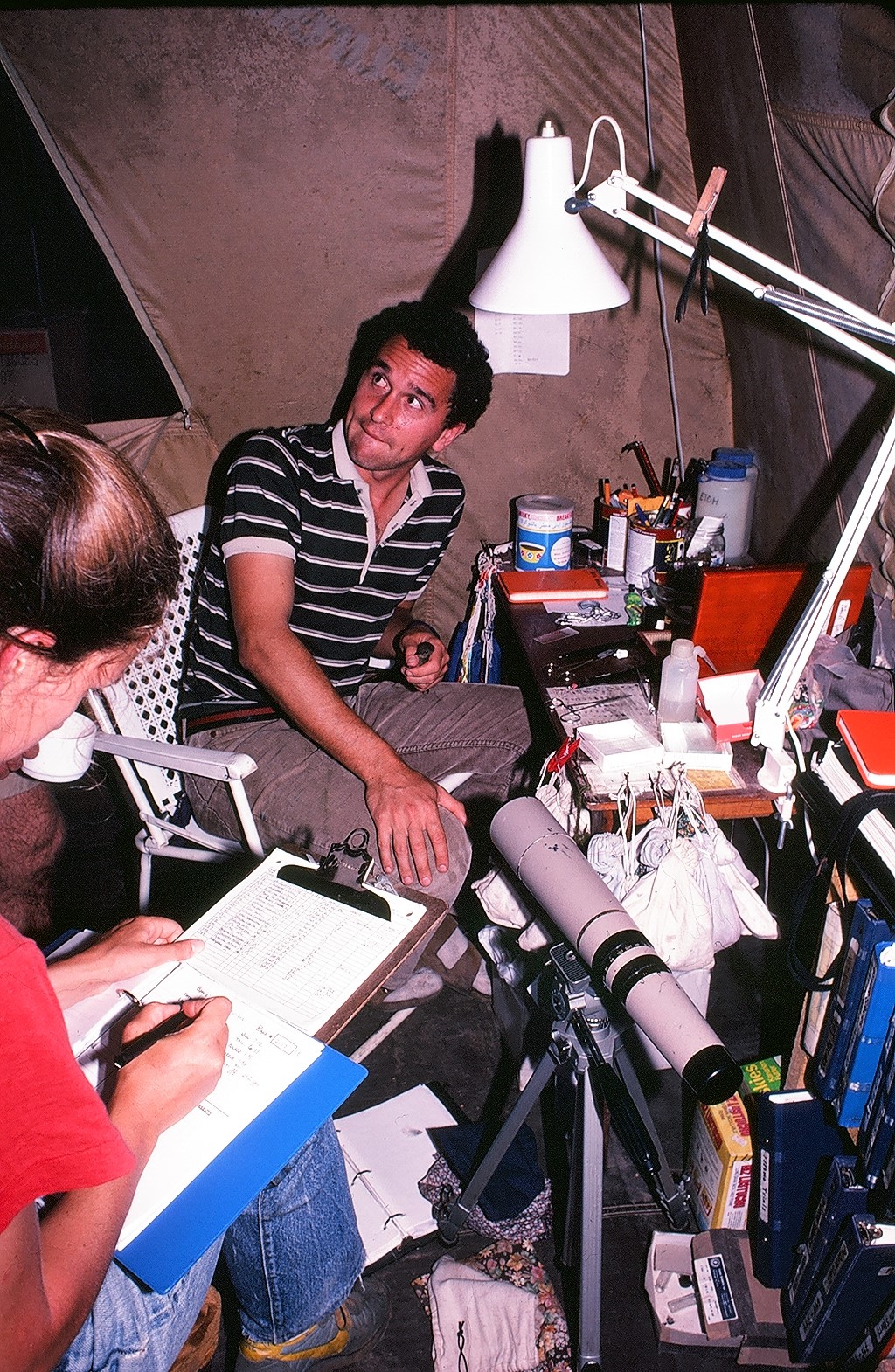

Then he caught a break. Acting on a tip from locals, he found a forest swamp that perfectly matched a description from a prior study on the birds. The swamp was full of sedge bushes, seedcrackers’ primary food source. Smith immediately put up nets. Within an hour, he had three birds. Eventually, he caught about 80, a sample size large enough to study.

Smith’s observations shed light on a curious anomaly described in a 1924 paper: Unlike every other bird known to humans, some birds have large beaks while others have smaller beaks — and the differences are not sex-based.

It was the beginning of years of research. After securing funding from the National Science Foundation and National Geographic, Smith spent three years working out of a makeshift tent in the rainforest. That first trip also marked the beginning of a career-long love affair with Central Africa. The affair reached new heights in 2015 with the launch of the Congo Basin Institute — a center for education and science that aims to transform the region for people and wildlife.

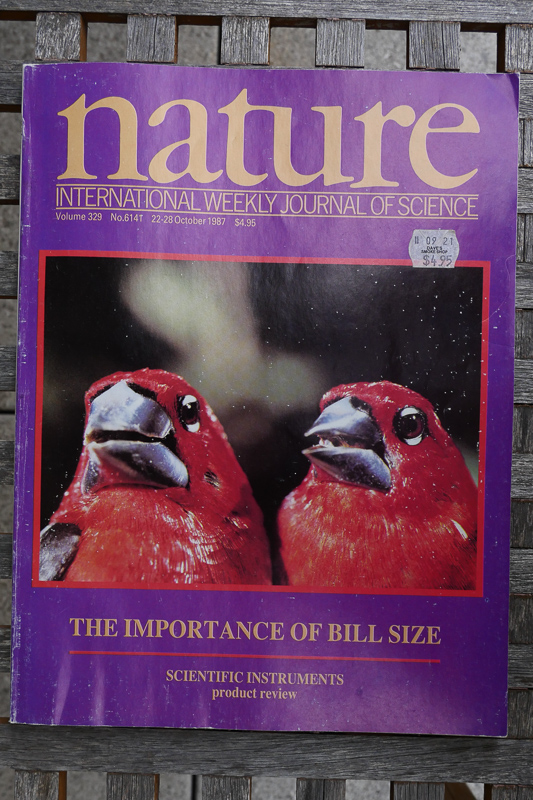

Smith’s seedcracker research was eventually featured in a 1987 front-page article in the prestigious science publication Nature. Smith had discovered that the difference in bill size correlated with food requirements. Small-billed birds were efficient eaters of small seeds. Larger-billed birds specialized on larger seeds.

Now, after three decades of advances in technology and genetics, he has found the biological source of the differing bill sizes. Using the latest genetic techniques to sequence the seedcracker’s genome — its entire set of chromosomes — Smith and a team of researchers identified the specific gene responsible in a new Nature article, published today.

The gene, known as IGF1, is basically a growth hormone, Smith said. It’s the same one that determines size in dogs, from Chihuahuas to Great Danes, but completely different from the genetic mechanism that determines beak shape and size in other birds, including the Galapagos finches famously studied by Charles Darwin.

“We’ve only scratched the surface,” Smith said. “Now others can look for this gene in different species of birds and see how it may play a role food habits and even speciation.”

Smith, who is a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology and director of the Center for Tropical Research, attributes his success to determination and “thinking big.”

“There’s a certain conservatism, especially with some major professors, to say ‘oh, just do something practical that you know you can get done,’” Smith said. “I’m the opposite. Reach for the stars. Even if you don’t get there, you tried to do something unique.”

Previous to Smith’s seedcracker research, other researchers had assumed the difference in bill types represented two distinct species or was some kind of mistake. Smith investigated further, driven by curiosity and close attention to details.

Those characteristics may be written into his own genetics.

Growing up outside of Chicago near Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore, a park on the southern shore of Lake Michigan, he was like other kids in many ways.

“I spent almost every day barefoot, running around in the woods collecting pollywogs, butterflies and lizards,” Smith said.

Not every kid uses plankton nets and microscopes to examine what they catch, though.

“I set up a little lab in our laundry room and kept detailed notebooks with drawings of all the cladocerans and copepods,” types of tiny aquatic crustacean. In first grade, he did a book report about white sharks. It was an inch thick.

Throughout his career, Smith has steadfastly refused to discard things of potential future value. Because of the feathers he kept over the decades, he has amassed the world’s largest collection of feathers at UCLA. That still-growing collection is an integral part of the Bird Genoscape Project, which uses genetic material in feathers to map the migratory routes, breeding grounds and areas of importance to North American birds. The findings enable conservationists to focus on protecting the most critical locations for the survival of species such as yellow warblers and endangered willow flycatchers.

It took years of work with African communities, government officials and nonprofit organizations to establish the Congo Basin Institute. But that work is already paying off. For the past two years, UCLA student teams traveled to Cameroon to research ways of making the ebony industry environmentally and economically sustainable. Students from UCLA and Cameroon teamed up to open and upgrade a long-shuttered research station in the Dja Reserve. It now serves as a place for field research and field classes while also acting as a deterrent to poachers.

“I want to provide the kind of facilities I didn’t have when I went to Africa,” Smith said. “I just had a backpack and little guidance or support.”

Though patience and a meticulous nature have been Smith’s allies, careful planning and teamwork also play an important role. The new paper “felt like closure” on the seedcracker, Smith said. As he looks forward to his career’s eventual end, he is trying to bookend other beloved projects. That means preparing the next generation to run major science initiatives like the Bird Genoscape Project.

“I feel secure because I have really good former researchers that are now professors who can carry it forward,” Smith said.

Perhaps the largest remaining piece of the puzzle will take Smith back to where it all started.

“For me, the big challenge now is the Congo Basin Institute,” Smith said. “It’s not just a one-off in Cameroon but a network across Africa. That’s my passion.”

If past is prologue, there’s a good chance he’ll make it happen.